I’m almost feeling like a Seattle native when I take the bus to downtown. I stand nonchalantly by the bus stop, like the old pros, and I don’t stare at the bus schedule I’ve hidden in my pocket. The morning buses are crowded, with a wide range of ages and skin colors. Some people read, others hunch over their smart phones and a good percentage stare ahead or out the window, the bus ride their quiet transition to the work day.

Many of us disembark at the Convention Center bus stop and on Friday I joined the throng of AWP conferees going inside. We’re easy to spot, with lime green lanyards around our necks with our nametags attached. The convention center is an enormous building with rows of escalators and crowded coffee shops and polite guards checking to make sure that we are indeed wearing our lanyards when we get off on the fourth floor.

Last year Stephanie Elizondo Griest joined the SLU community as the Viebrenz Visiting Writer and she and I became good friends. She’s now teaching non-fiction at UNC Chapel Hill and I was looking forward to seeing her again and hearing her speak at a panel discussion called “Family Trouble: Memoirists on the Hazards and Rewards of Revealing Family.” We had just enough time to exchange a hug before the session began.

Now I’ll be honest. I probably wouldn’t have gone to this session if Stephanie hadn’t been on the panel. Memoir is not my favorite genre and, well, there were 24 other sessions to choose from in that time slot. But the memoirists were all eloquent and passionate and each one had my total attention. Ralph Savarese (Reasonable People) told of adopting a severely abused and autistic boy and wondering if the memoir he planned was a violation of his son’s privacy, even as he hoped it would show that autistic children did indeed have emotions and empathy. Amazingly, by the time Savarese finished writing his memoir, his new son had learned to read and “talk” by using a keyboard. The last chapter in the book is in the son’s words. One author told of writing about incest and another writer said, “What can be gained by revelation?” She said to make a good story a memoirist must know each family member deeply. “I forced myself to love every character.”

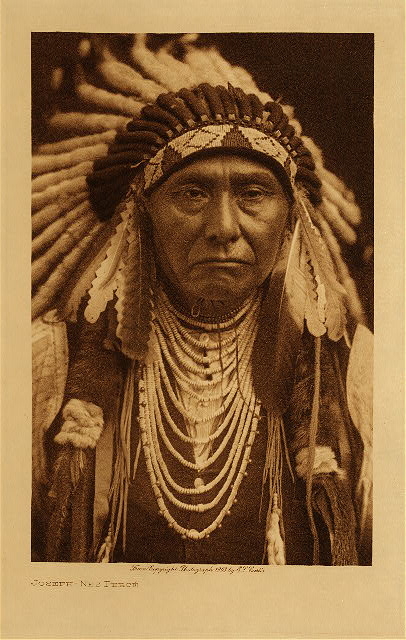

I left that session before the Q and A ended to rush a few blocks to the Seattle Public Library for an appointment with Jodee Fenton, the head librarian in Special Collections. She was taking time out of her busy day to show me volume 8 of Edward R. Curtis’s magnificent set of twenty books, The North American Indian. Curtis’s photos are iconic sepia-toned profiles, his Chief Joseph photo the most famous, perhaps, of all photos of Native Americans. For historians, art historians, anthropologists and plain old Americans, the Curtis photos and books are a treasure trove of art and data. They’re also extremely rare, with about eighty complete sets in the world. The last time a set sold at auction it went for 1.8 million dollars.

My friend Dave MacDonald joined me and we waited while Ms. Fenton went into a vault to get out the book. I’d asked to see volume 8 as it has photos of the Nez Perce people and in the summer I work in the part of Idaho that was their homeland for hundreds of years. The volume arrived, carefully placed on the top of a wheeled cart. We headed to the elevators to go to a viewing room and a couple of men saw our procession. “Is that the Curtis?” they asked. For some Westerners the Curtis books have the status of a Gutenberg Bible.

In the viewing room we were asked to sit facing the book. Each volume of The North American Indian consists of a very large portfolio of photos and a smaller bound book of text and photos. Curtis insisted on the highest quality paper and fine leather bindings. The set of books was so expensive that only libraries, universities and the very wealthy could afford a subscription. Curtis hoped to publish one new book a year but problems with financing and his own mental health slowed down the project. Timothy Egan’s new biography details all the successes and setbacks (Short Nights of the Shadow Catcher, The Epic Life and Immortal Photographs of Edward Curtis).

Dave and I sat still as Ms. Fenton held up the first photograph, the famous portrait of Chief Joseph. The detail was astounding and each line of Chief Joseph’s face told of his sorrow. He died a year after Curtis took the photo and some said he died of a broken heart. He’d petitioned the US government for years but his band of Nez Perce people were never allowed to go home to their ancestral lands in the green Wallowa Mountains of Oregon. They languished in the dry, hot flatlands of their resettlement land in Oklahoma.

Ms. Fenton put the Chief Joseph photo away and worked through the portfolio, carefully removing the yellowed tissue paper between each photo and lifting up the artwork for us to see. It reminded me of being present at a Japanese tea ceremony, where each object must be honored and handled in a special way. Particularly interesting were a couple of photos that showed people and horses or boats in the almost dark. They were incredibly dramatic and looked like oil paintings. Volume 8 was published in 1911 and I know Curtis didn’t use a flash so he may have set his camera for the low light or manipulated the photos when he returned to his studio in Seattle. None of Curtis’s photos are candids; he carefully set up each shot and asked his subjects to wear traditional clothes. But the photos didn’t seem staged. Most showed the dignity of each person, something Curtis spent hours and hours trying to capture.

After almost an hour we’d looked at all the photos and Ms. Fenton opened up the box that contained the text that went with the folio. She showed us the gold banding on the spine and the thick creamy paper of the pages. Curtis and his assistants gathered as much data as they could from each tribe—language, customs and even music. We didn’t have time to read the text but Northwestern University has scanned the books and they’re on line at http://curtis.library.northwestern.edu/

When it was time to go we thanked Ms. Fenton as she rolled the cart into an elevator. She obviously loves sharing the Curtis books, the most valuable collection in the library. She told us that the Seattle library probably got a deal on buying the set as Curtis wanted the people of the city to have access. They may have paid $3,500 for the books, a good investment. Not that they’re for sale. She told us, proudly, that anyone can come to the library and get an appointment to see the Curtis books. In many institutions only researchers have access.

Dave and I rushed off, he back to work for the city of Seattle, and me back to the conference. I thought of those photos for the rest of the day and the lost North America they tried to capture.

I shouldn’t have been surprised that my next event wasn’t on par with the Curtis photos. “The Art of the Book Review” wasn’t horrible but it wasn’t very well organized. I liked the passion of the panelists, people who obviously didn’t agree with Annie Proulx’s assessment (she said the only qualification a book reviewer must possess is the ability to read). Craig Teicher said a book review is good if you want to argue about it and Darcey Steinke told us she tries to find what is “strange” about each book, what is its life force.

Back outside for me, and this time I power walked up Pike Street to the Capital District to pay homage to the Elliot Bay Bookstore, Seattle’s premier independently owned book shop. It had a satisfactory cozy feel, with hardwood floors and lots of nooks and crannies and a little café downstairs. I reminded myself that I had to get all my belongings into my carry-on bag and limited my book buying to presents for my Seattle hosts.

My next event, “There She Goes Again: Women Writing Travel,” featured Stephanie Elizondo Griest again but I would have gone anyway as Pam Houston was one of the panelists and I’ve enjoyed her writing since her first book of short stories, Cowboys Are My Weakness. The panelists discussed why so few travel stories by women appear in print. In this year’s edition of The Best American Travel Writing only three of the nineteen essays were by women, and that’s been about the percentage for years.

It’s not that women aren’t writing travel essays. Lavinia Spalding edits an annual of the best of women’s travel writing, essays that haven’t already appeared in magazines, and receives hundreds of manuscripts each year. Discussion among the panelists didn’t come up with any solution to the shortage of female voices but they all agreed it’s best not to try to write “like a man.” Tracy Ross, who writes for Backpacker and Outside said her stories got better when she stopped trying to be Jon Krakauer. Some of the panelists said that it’s different being a woman traveler, that women have to be more careful, but Pam Houston, bold and funny, disagreed. “I’ve got a lot of guy in me,” she said, “even though I’m married to a man. I’m not afraid when I travel.” She also said that Cheryl Strayed’s Wild and Elizabeth Gilbert’s Eat, Pray, Love have sold more copies than any travel books by men so why doesn’t that translate to magazine stories?

Right at rush hour, both in the Convention Center and outside on the city streets, I tried to meet Canton friends Kate Harloe and David Pynchon. My awkward, super-slow texting skills didn’t help the situation but eventually we all found each other and assembled at a Thai restaurant for dinner. Kate moved to Seattle last year after graduating from Hamilton College and David is a recent SLU grad. Both of them started out working in a bike shop and they’ve found internships with innovative, young companies, places they hope will hire them soon. They told me Seattle is filled with young people, and growing rapidly. It’s a great place to be, for now.

- lopezbook

Photo: coconinoco

The last event of the evening for me featured Gretel Ehrlich and Barry Lopez. For Ehrlich’s newest book, Facing the Wave, she traveled to Japan to meet people in areas damaged by the tsunami. Years ago I read and admired Arctic Dreams and Of Wolves and Men by Lopez. Both authors write often for widely read magazines.

I’m avoiding using the words “environmental writers” as I don’t want to pigeonhole Erhlich and Lopez, but I think I can say it proudly. These are two writers who try to have their writing change the way we view the world. Ehrlich spoke first, reading an essay about the devastation of climate change in Arctic villages and reminding us that the Arctic drives the climate of the world. It’s not looking good.

Lopez spoke deliberately, like a minister, and his voice reminded me of his prose—thoughtful and handsome and measured. He read from his essay “Six Thousand Lessons.” I wasn’t at my best as a listener but I did hear some great phrases: “television, a kind of cultural nerve gas” and “as you grow older you realize if you write well at all it’s because somebody loves you” and a writer is “involved in the making of valuable patterns.” I did keep my eyes open for his 350 word story, a length suggested by Bill McKibben of 350.org.

After the talk I made a beeline to the bus stop. I needed to catch the 10:19 and I arrived with 4 minutes to spare. Feeling urbane I stood with a few other people and waited. And waited. And waited for far more than five or even ten minutes. No one else seemed concerned so I took out my new Ursula Le Guin books. “How do you like the conference so far?” asked a woman standing next to me. I don’t think she could even see my lime-green lanyard. We had a good chat about talks vs. panels vs. actually visiting with the friends who are providing a bed during the conference.

Finally, at almost 11pm, a bus arrived. There’d been a breakdown in the bus tunnel under downtown and the passengers already on the bus had sat until the next bus came along. They looked weary. I was just happy to cram myself onto the overloaded bus and head north to Lake City. It would be good to get a few hours of sleep before reversing the journey for the last day of the conference. I’d circled talks by Ursula Le Guin, Gish Jen and Tobias Wolf and, the grand finale, Timothy Egan and Sherman Alexie.